The elimination of typing departments happened slowly, and then quickly. It took time for offices to adopt PCs and understand what it could do for finance and accounting. Invisibly, a market for word processing was forming. When a word processing product at a cheap price point was finally built, adoption exploded. And as soon as executives, secretaries, legal departments, and others saw how easy it was to write documents, typing departments became superfluous.

As Steve Jobs famously said, you can only connect the dots looking back. In addition to being great personal advice, it helps to describe the fog we find ourselves until the moment a change happens.

My interest is understanding how AI will affect work with a mental model I call the Automation Chasm.

Word processing is a good example of what seems like a fast economic change that was hard to predict due to new technology. It may have been obvious what was going to happen, but impossible to know when or how. If you were looking from the commercialization of the PC to office word processing eliminating typing departments and changing other jobs, you might notice a chasm. That chasm gets smaller the closer we get to adoption of PCs across the workplace and the enhanced software capabilities of PCs. What makes the chasm interesting is that it isn’t comprised only from a product capability but also buyer beliefs and behavior.

Today generative AI brings newfound capabilities to computers around creativity. Some of the technical marketing jobs like content or ad copy writing are consequently under threat. Storyboard artists, graphics artists, and videomakers are similarly threatened by generative AI in other modalities like image, vector drawing, and video generation.

Change doesn’t always happen fast even if the product capabilities are incredible. Legal departments have only recently (in the last decade) moved from paper to digital. Healthcare is full of paper operations too, and many professions still use a digital version of paper like Word documents and PDFs, instead of digitally-native ways of storing and communicating information like tables, databases, and apps. In fact the entire B2B software-as-a-service industry has exploded primarily to facilitate the transition from paper to digital and beyond, a process dubbed “digital transformation”.

Why is legal or clinical so much slower to automate than marketing, despite both being squarely in the crosshairs of creative computing? It starts by looking at the complexity of a job and its workflows. The more complicated the workflow, the less willing people are to change it. Legal and healthcare have the added friction of mistakes having severe consequences, so any change comes with extra scrutiny and added complexity in the workflow for safeguards.

But automating an existing workflow done by a human is not the only path to automation. Some of the greatest successes of automation come simply from standardization and straightforward application of technology. Instead of inventing robots to pack ships perfectly with goods to be transported, we standardized shipping containers and the trucks, ships, and railway cars which transport them. The challenge shifts from technology to economic incentives. While both can be infeasible, the entire idea of startups is predicated on aligning economic incentives to create change in markets.

Disruptive technologies eventually make their way into all areas of work. What governs whether disruption happens today, tomorrow, or in a decade? Workflow complexity is one variable that translates to a switching cost from the status quo. We touched on risk appetite, a specific case of more general cultural barriers to change. Workflows where multiple people transact with each other as part of a network bring some of the highest costs to change. This starts to sound familiar—these are all business moats. The moats of existing software companies give a signal as to when disruption will happen, and also where. Niches which have no strong deterrences to change are ideal starting points, sometimes because they simply have nothing to change from. This simply follows from the classics: disruption theory by Clayton Christensen, the physics of market adoption described by Geoffrey Moore, and the sources of sustaining business power (moats) defined by Hamilton Helmer.

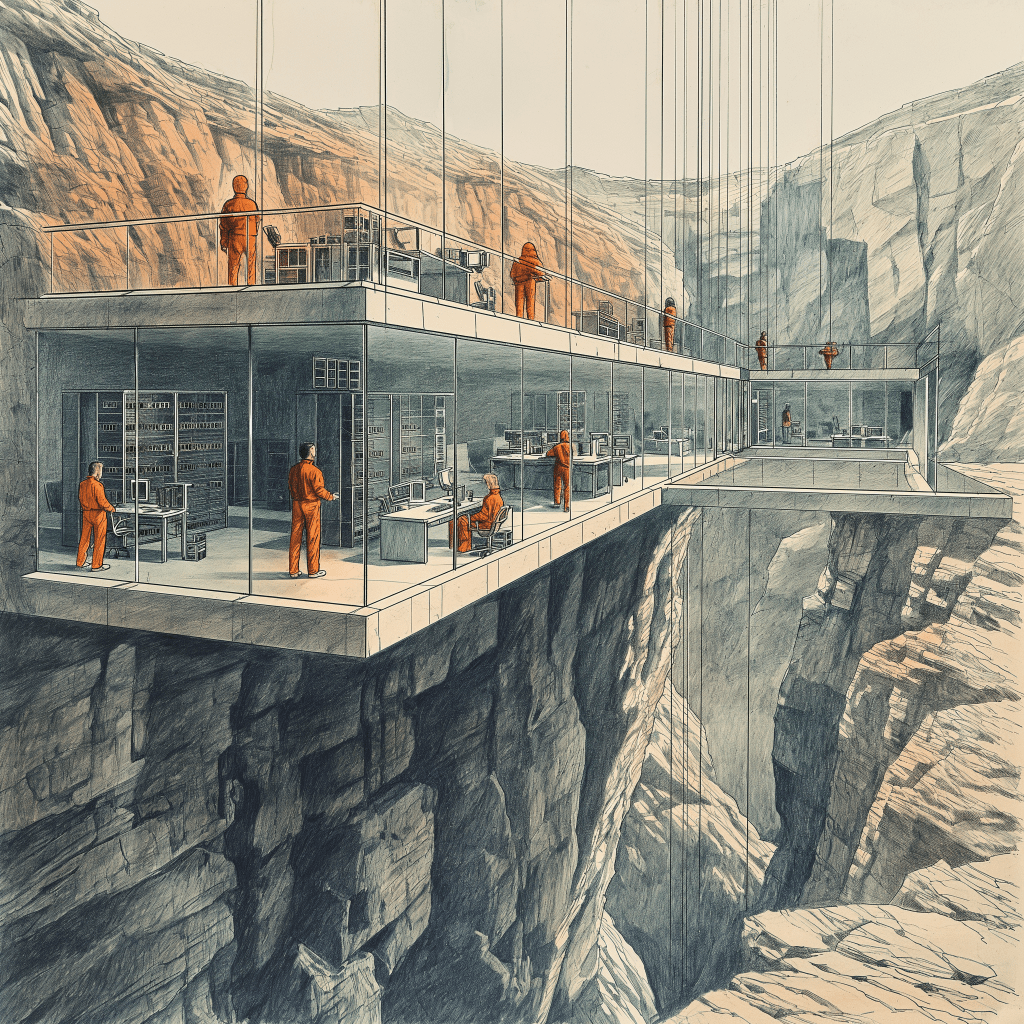

The Automation Chasm is about the sum total of hurdles to automation. It is both the complexity of building the product and the costs of changing buyer behaviors that create the chasm. I’ll talk about three examples: a fun and illustrative example around autonomous vehicles, and two other examples where I can speak from experience, contracts automation and autonomous delivery of therapy.

Autonomous Vehicles

We’ll start with a fun example around autonomous vehicles (AVs).

Transportation has some issues:

- Cost: It costs a lot to own a car, and ride sharing confers little cost savings for most. Most of the cost is in human drivers, especially in ride sharing.

- Safety: humans crash cars at an unacceptable rate largely because they lack focus and attention either through distraction, sleep-deprivation, or substance use. Self-driving cars have the potential to eliminate this problem.

- Convenience: most humans find driving boring. Humans riding in a car can do other things if their vehicles drove themselves.

The market of car-buyers will happily accept new autonomous features for the products they currently buy (a car they drive manually). Cruise control and lane assist can make an incremental impact to the problems sketched above, but this pales in comparison to the impact AVs could have.

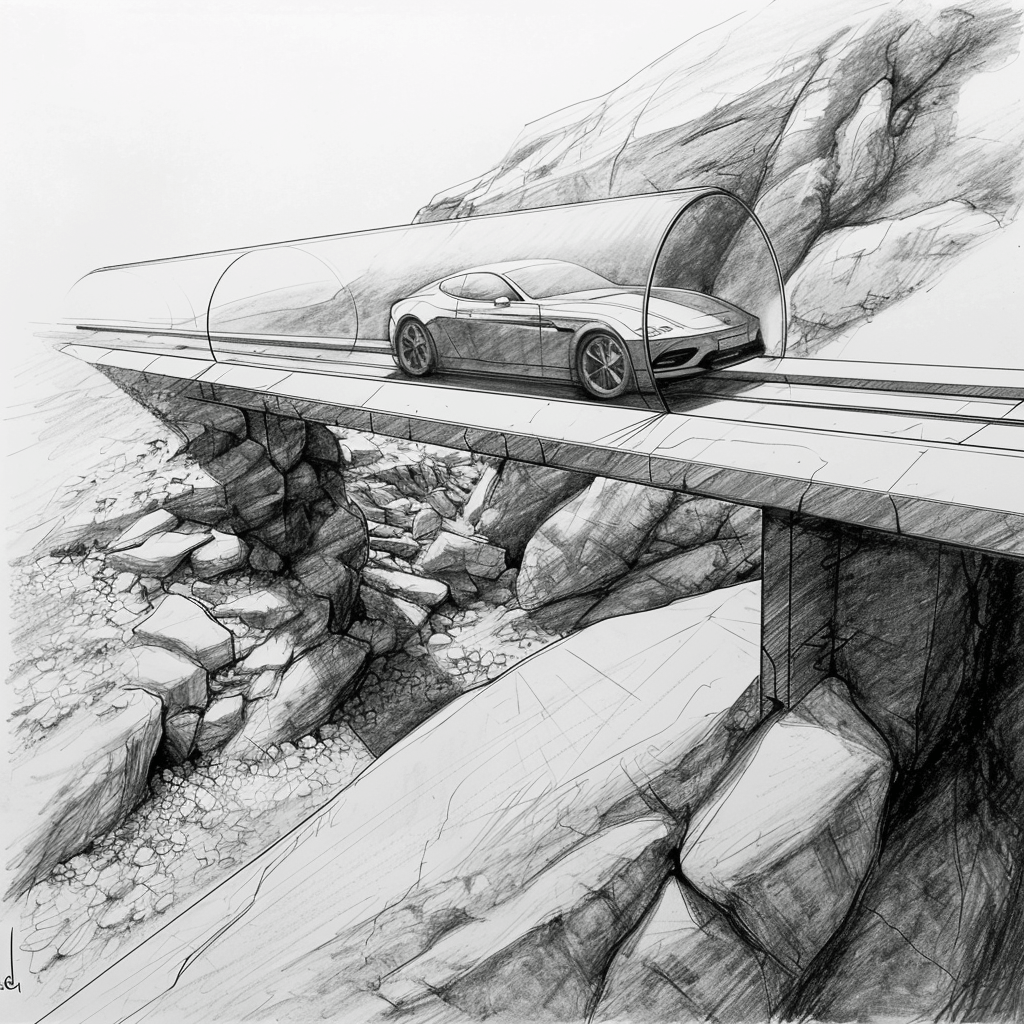

Buyers of AVs require that the product fully replace their “workflow”, the manual driving of the car. The workflow complexity comes directly from exposure to the raw complexity of the world. This is the reason why AVs are still under development even after over $100bn in investment: the workflow complexity is incredible.

Let’s consider alternative ways to solve the problems that AVs solve. Trains, subways, and light rail don’t remove the driver but have the potential to fully solve every pain point around cost, safety, and convenience. But focusing on eliminating the driver would be misguided. It is parts of the workflow we want to eliminate, and railway vehicles don’t have the same complex interaction with pedestrians or other vehicles as cars by construction.

Anyone familiar with the buyer of a subway system knows that this doesn’t get us out of the automation chasm, it just pushes the challenge from product development to market will. How many governments and taxpayers are ready to buy such a large and expensive product? Not many, and while niche markets where buyers are more amenable do exist, the laws of physics and construction are significant barriers to changing buyer behavior at scale. It is unlikely that this disruptive product will catch on.

AVs are interesting because spending hundreds of billions of dollars to develop them is easier than introducing a stripped-down version of an AV (a vehicle on rails) and selling them down-market to the taxpayer. This exception that proves the rule—automating existing human workflows is an exceptional undertaking.

Autonomous Contract Negotiation

Contracts are a foundational piece of infrastructure that run society. Without formal agreements collectively enforced, the economy itself could not function.

But there are several problems with how contracts are negotiated today. While we have digitized many of the workflows, they are in effect still digital representations of paper processes.

Many contracts happen between businesses, and for buyers of contract negotiation services there are several issues:

- Time: there are at least two sides to every negotiation, and going back and forth means lots of waiting and ultimately a delay in a signed contract. An automated solution could take a process that happens over days or even weeks down to seconds.

- Cost: lawyers bill by the hour and negotiations take time. There are at least four sides to any negotiation, a lawyer and a client with negotiation preferences for each party in the negotiation. The further away two parties are in expectations for the terms of the contract, the more back-and-forth there will be. This translates directly into higher costs. An automated solution could reduce these costs by orders of magnitude.

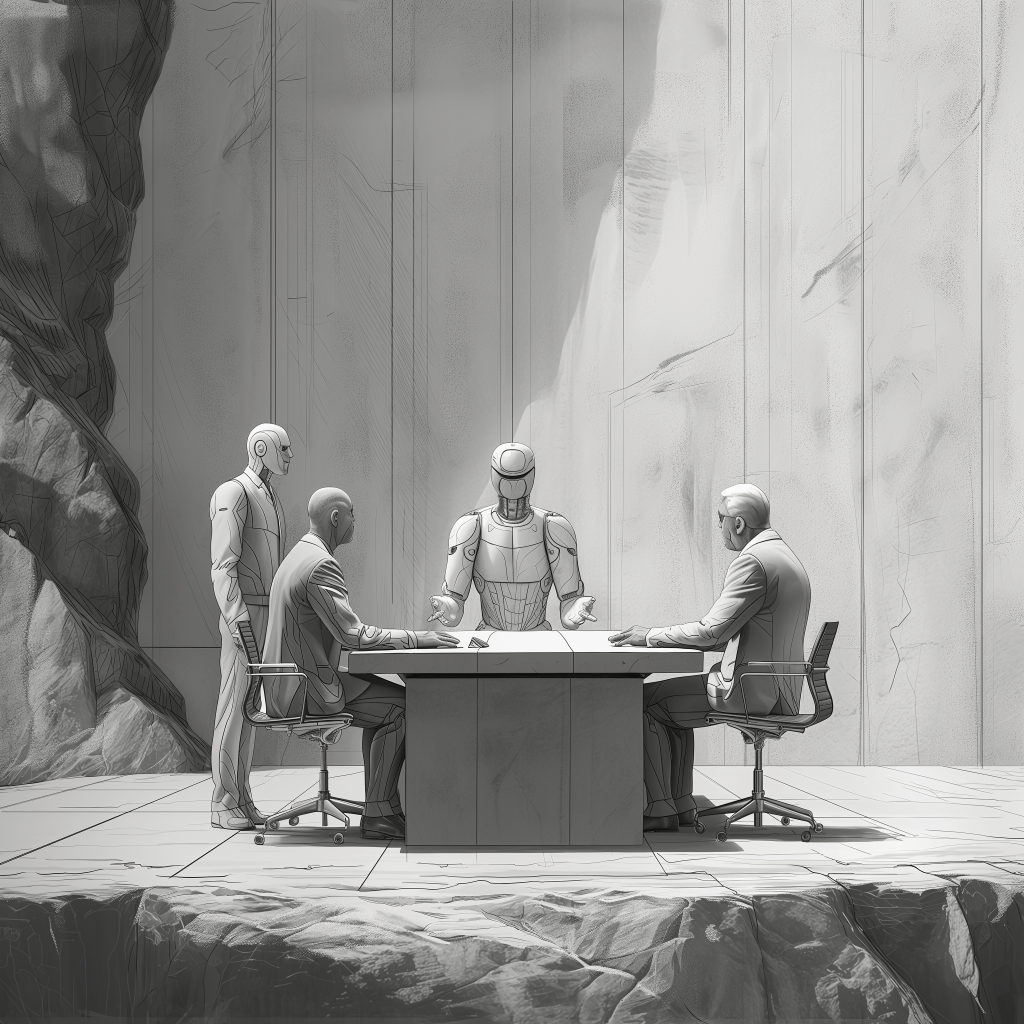

The workflow for a negotiation on the face is fairly simple: one party proposes terms by sending a draft contract to the other party, the other party “redlines” the draft by crossing out certain terms and replacing them with their preferred term before sending it back, and back and forth it goes until both parties agree and sign.

Just as it would be folly to imagine driving as simple as pushing pedals and turning a wheel, so it is with contracts. The true complexity comes in the terms in these contracts, the fact that everyone has their own preferred language, and the centuries of precedence built up in the practice of law which defines contract language so poorly that only a court can resolve ambiguities. And that is only considering a human’s interaction with the law—we haven’t even defined interactions between lawyers. Directly automating the workflow of a contracts lawyer may be about as difficult as automating a human driver.

Is there an alternative to solving the customer’s problems? Perhaps there are buyers of negotiation services that don’t require the perks of a human lawyer, like customized language and preferences, leverage from special negotiating skills, and trust in a highly-competent professional.

If we hypothesize that these buyers exist somewhere, perhaps in a niche market where buyers are sensitive to cost or time, then automatic contract negotiation starts to look achievable. Just like putting cars on rails, the key insight is in bounding complexity with standards. If all negotiating parties in a market segment agree to note their preferences against standardized terms of a contract, an automated system could simply collect preferences and immediately draft a contract agreeable to both parties.

This sounds great. We’ve turned an impossible technology problem into one that is quite achievable to implement. But again we see the challenge go from product development to market readiness. Does there exist a market for such a service? How might one bootstrap a network of transacting parties? Building networks and marketplaces is a very challenging business problem.

We see that the automation chasm for contracts automation is formed due to incredible product development complexity and a challenging market penetration problem with a simpler product that is much more feasible to build.

In the case of AVs, the “simpler” alternative of putting cars on rails to create subways didn’t require automating away the driver. There is a similar middle ground for contracts automation: lawyers that negotiate contracts in a highly-structured way which makes their operations much more amenable to scaling and therefore cost reduction. Current buyers of contract negotiation services are happy to pay less. They can still get customizability and negotiating leverage at a higher price if they’d like, and they can trust that a highly-competent human lawyer will always be supervising. Ontra, a very successful startup where I worked on contracts automation with AI, implements this exact strategy in the financial services domain.

Autonomous Therapy

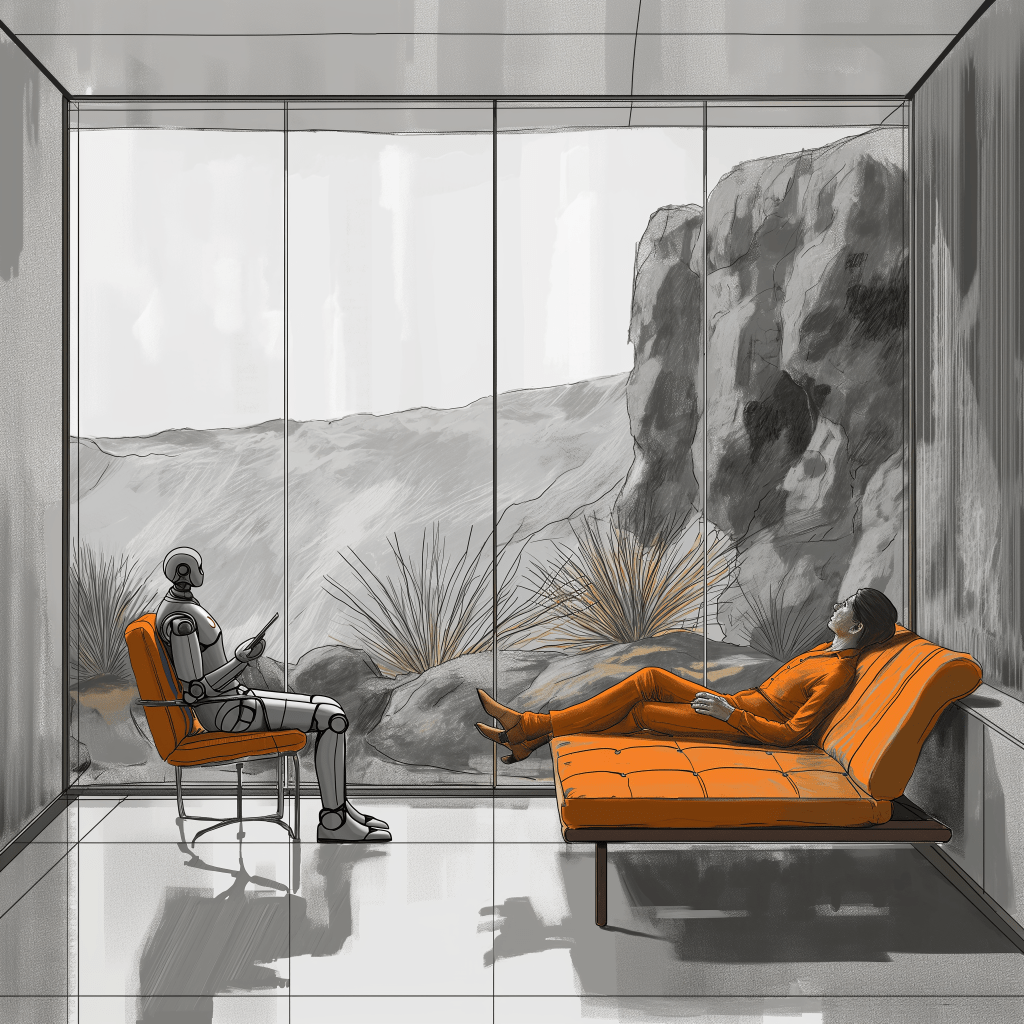

Therapy today has a massive problem of supply and quality, both which impact costs and revenue for mental healthcare providers and insurers. There aren’t enough therapists to meet demand, and poor quality comes largely from therapists who don’t practice scientifically proven evidence-based treatments. An autonomous therapy product could add significant supply while delivering high-quality therapy that is scientifically proven to work, thereby reducing overall costs of healthcare as it leads to fewer hospitalizations and requires less operating cost to implement. For patients, low supply inflicts both financial costs and limited access (a cost to their health).

While evidence-based therapy does have a highly-structured procedure, it’s tough to even imagine the therapy workflow as simple. Patients interact with therapists often through video chat, voice, or in-person sessions, though sometimes through text messaging. Aside from the therapy itself, the administrative workflows around managing patients is fairly complicated and tedious. As in the cases of AVs and contracts, mistakes have incredible costs—sometimes to human lives. The automation chasm around product development is formidable.

The simplified product derives from the structured regiment of evidence-based therapy. This therapy is so structured that a pen-and-paper workbook provably makes significant impact to a patient’s mental health equivalent to medication or therapy with a clinician.

Translating a workbook into a text-based therapy session delivered via AI is far more achievable than automating the full workflow of a therapist. But again, is there a buyer? Are individual consumers willing to buy therapy delivered in a more limited form? Will large health systems or self-insured companies be willing to buy a more limited mental health service to add to their healthcare offerings? Healthcare systems have operations that work today and the technology that supports them make for very sticky products. There is immense cultural inertia around how therapy is delivered and who is to be trusted to do that effectively. All of these present formidable challenges to changing the status quo.

So again we see that the automation chasm consists of both an incredible product development cost and the need to significantly change buyer behavior. The story for automation in mental healthcare is just beginning, and one that I’m currently working on.

Closing Thoughts

The Automation Chasm is a useful concept to imagine how AI automation might happen. Successful new technology threatens the status quo and sometimes catalyzes massive change in the economy. Both tech builders and workers are keen to understand just how that automation will happen. Will it threaten our jobs or push us to new heights through assistance? The question is just as much about product and market incentives as it is about technology.

We’ve seen that direct automation of jobs as they are done in the economy today is extremely hard. Part of that is due to job workflows that rely on a human capable of relatively high levels of creativity even for simple jobs like driving. Then there are the barriers to change in buyer behavior. People like to trust humans for important work, and there’s always friction to changing what is already working even if it would be faster, cost less, or be more convenient in the long run.

But automation doesn’t have to happen by direct replacement of human work. If market conditions allow for a product implementing a simplified job workflow that is more achievable to develop with current technology, then economic change happens through changes in buyer behavior in niche markets where alternatives are unattractive if they exist at all. This is essentially the story of how startups succeed.

There isn’t always an automation chasm. Marketing is one area where generative AI threatens stability to the status quo. The ability for AIs to generate customized and eloquent paragraphs or beautiful images on any topic or brand means marketers have a new alternative to hiring talent for that work. Just like word processing and PCs once eliminated departments of typists and secretaries for executives and a number of company departments, so too might generative AI eliminate content writing or ad copywriting for marketers.

Big companies also face automation chasms, but not always. Established market leaders may choose to put their dollars into improving their internal operations with automation, robots in Amazon warehouses being a classic example. While they face many of the same technological challenges of automating existing workflows, visionaries at the helm of large enterprises can sometimes overcome internal barriers to change. This effectively solves the analogous problem to changing buyer behavior through self-disruption. Because these companies employ significant numbers of people, such changes can effect great economic change similar to disruptive startups.

Despite these caveats, the concept of the Automation Chasm shows us that automation is hard even with advanced new technology like AI. It isn’t just a technology problem but also a problem in changing people’s behaviors. And changing people’s minds might be the hardest problem of all.

Leave a comment